KI Dairy Part 3 - Gunn's East Wickham Factory

Pic supplied by CG Stubbs.

The King Island Courier wishes to acknowledge the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery and researcher Jill Cassidy for her work 'The Dairy Heritage of Northern Tasmania: A survey of the butter and cheese industry', published in 1995, from which much of the below material was drawn.

PART 3 - The outbreak of the Second World War changed the island’s dairying industry yet again. The new company King Island Cooperative Dairy Products Ltd. with a new manager soon found itself in difficulties. With the shortage of labour brought on by service enlistments, supplies to the factories were limited. To rationalise expenses, all butter making was centralised at the old Cooperative factory at Loorana and all cheesemaking at Gunn's East Wickham factory.

By 1944, a new brick building was erected at Gunn's East Wickham factory and the other cheese factories, including the large Seaview (or Ascot) factory, gradually closed. In 1942-3 Ascot had produced 135 tons of cheese, compared with 359 tons from the other factories including an amount made at the Loorana butter factory. The new brick building at East Wickham had a whey separator installed and produced up to 160 gallons of whey cream a day. The Wickham factory was potentially the largest supplier of cream to the Loorana butter factory, which made the cream into cooking butter. But despite, or perhaps because of, rationalisation and reasonable production, in 1943 the company had a debt of £15,000 to the Agricultural Bank and it was forced to devalue its shares by 50%.

Production at the East Wickham cheese factory gradually increased from 359 tons in 1942-3 to 535 tons by 1945-6, making it the largest cheese producer in the state. The factory in the spring, operated two shifts, making cheese after each milking, not just in the morning.

However, there were problems with marketing and from 1945 the company worked in conjunction with Kraft Walker Cheese Co. giving Kraft Walker Cheese a controlling interest. Kraft wanted the island to supply 30,000 gallons of milk in the spring. The company found cartage on King Island expensive, and it employed two men full-time to make export crates to ensure the cheese arrived in Melbourne in good condition. In a refit, Kraft bought new equipment, including a large boiler, and was told by Holyman that their ships would be unable to handle the weight of the boiler. The relationship fell apart. Kraft sold the new equipment to a Strathmerton factory and on 30 June 1947, all cheese production stopped at East Wickham and the excess plant was sold.

The reconstituted King Island Dairy Products Co-operative Society Limited concentrated on butter making as there was unlimited strong demand after the war in Europe. The Federal Government Subsidy on butterfat rose so sharply in1948-9 that the independent Last family were forced to abandon cheesemaking. In 1942-3 the Loorana factory had produced 187 tons of butter and by 1948-9 production was at 468 tons.

The debt to the Agricultural Bank was soon paid off. With the new Soldier Settlement scheme in operation by the 1950s, supplies increased and by 1955 the factory and plant were no longer fit for purpose and inadequate. With the help of a government grant, a new factory was built in 1956 at a total cost of over £100, 000. This included provision for a general store as the company sought to diversify. It also

took over agencies for petrol products and later fertilisers and machinery and began to trade in cattle and wheat. In 1959 the factory reached its peak number of 197 suppliers with 920 tons of butter being made. Peak production of 1070 tons was reached in 1964-5.

However, the industry then experienced a steady decline as many older farmers left the industry and the approaching entry of Britain into the European Common Market meant that the butter market was becoming uncertain. By 1974 there were only 61 suppliers and the factory output had declined.

PART 2 - GIPPSLANDER J Blain was employed by Jane Snodgrass as cheesemaker on her Loorana farm to the east of the North Road. This was to have interesting consequences. Blain had been trained along with, several Western District farmers by the Gippsland and Northern Cooperative Co., which then marketed the product. Blain subsequently trained many of the island's cheesemakers and much, and possibly all, farm-produced cheese from the island was marketed through the Gippsland and Northern Cooperative. Blain left around 1916 and bought a farm at Yambacoona. Before Blain left to start up on his own, he trained Reg Humphreys who continued to make cheese for Jane's son, Peter, for many years. In the 1920s Peter and his wife Eleanor had a contract to supply as much cheese as possible to the London market.

The Weekly Courier reported that in April 1914 Will Bowling set up what was called the first cheese factory. The cement brick building, was approximately 6m by 9m and was on Bowling’s farm to the east of North Road at Boobyalla. Arthur Hardman bought the property in c.1917 and kept the factory going, employing Ted Wicks as a cheese maker. It closed at an unknown date, although before 1934.

In 1919 Mr W. E. Bowling., the proprietor of the Boobyalla Cheese Factory, received an order for cheese from the Australian Governor General and Sir Francis Newdigate the Governor of Tasmania praised the cheese publicly and in private.

Before 1919 Blain was making cheese again. Bill Bell and in the early 1930s Horace Connolly worked as his cheesemakers. His factory was to the south of the East Wickham Road at Yambacoona.

Brooklyn Cheese Makers appears to be the 3rd Cheese factory on King Island and in 1916 was owned by Mr W. E. Looker. It was situated on the south side of the Currie-Fraser Bluff Road, commonly known as the Fraser Road. Looker engaged Mr. J. Richards to trial cheese-making. The milk came from 21 of his cows and 40 cows owned by adjacent settlers. Mr. Looker told the King Island News “My total output of cheese for eight months was about 5½ tons, practically all of which was sent to Melbourne, where it met with ready sale. Notwithstanding that the supply of milk was ample and the prices the cheese brought in Melbourne were satisfactory, I found that the cost of production and other expenses were making a great inroad on my profits… I found it necessary to close my factory and dispose of the plant.” Most of the costs after manufacture that eroded profitability were the lack of a regular shipping service, freight and wharfage charges and appropriate storage facilities. Looker turned to year-round butter making, potato crop growing and sowing Algerian oats.

In the 1920s Holland and Haines set up the biggest dairying property on the island at Koreen, with four share farmers supplying milk to the factory to the south of Haines Road. Several houses from the Closer Settlement scheme in Grassy were relocated “to establish several dairies and equip a cheese factory.”

By 1921 the Weekly Courier wrote that "the local butter and cheese factories are famed for the excellence of their product. Part of the reason for this is said to be that the product remained unpasteurized and therefore the natural flavours remained.”

In 1922 when the butter factory was turning out six tons a week, most of the big dairymen had their own butter churns and there were several cheese factories. These private producers participated in the expansion of dairying in the 1920s. In 1924 the island exported 300 tons of butter and 130 tons of cheese, a record which remained for several years. The returns from dairying were so good that many large pastoral estates converted to dairying and by 1931 there were over 5000 head of dairy cattle on the island.

The East Wickham Cheese Factory was started in 1928 and managed by Ernie Fisher. However, in the 1930s there were big changes, due to the onset of the depression. The butterfat price dropped from eighteen pence a pound in 1929-30 to seven pence a pound by 1933 (sixpence if the factory carted the cream) and many dairy farmers were soon in extreme difficulties, particularly those with smaller farms which were no longer viable. As in other Tasmanian areas farmers were forced off their farms, while many others only just survived.

While the butterfat price was so low, cheese became much more attractive and there were soon moves towards establishing more cheese factories on the island.

Part of this push for cheese came from the poor management of the butter factory. Cheese had been made at many cheese factories across the island since 1912. In 1933 the factory had produced only 6% Choice butter, compared with 56% in the previous year. The inspections conducted by Dairy Officer Sandman in 1934 were scathing stating the cream pumps were "in a shocking condition" and "he had never seen packing in such a filthy state”. His supervision of manufacture led to a marked improvement in quality. His relationship with the manager, Brown, and the Chairman of Directors, Clemons, had been antagonistic. When he left, the quality declined once again. Suppliers voiced complaints and by 1934 they were openly questioning the weighing and testing at the factory. Less than 50% of suppliers were said to have confidence in the manager. An investigation showed that Brown had falsified returns to the Department of Agriculture to mask a high over-run. He pleaded guilty at the subsequent prosecution.

The poor quality of butter was also due to the quality of cream being supplied to the factory, and little desire to improve the premises. One of the biggest shareholders decided to take action. In 1933 (Archie) Gunn, a former director of the factory, withdrew his supply and constructed a cheese factory at Reedy Lake, later renamed Penny Wickham. The following year Gunn Pty Ltd began both butter and cheese manufacture at Seaview (also known as Ascot), utilising and extending the old Bowling-Hardman building, which he had purchased from Hardman along with a few acres on which to build a house for the manager and other necessary buildings. He added a huge room with two big churns for butter making, two offices and a garage to service his trucks. This new venture was only two kilometres from the Cooperative's Loorana factory. It is noted that he obtained his butter licence just in time as by 1936 new butter factories had to prove their operation was in the best interests of the industry, and the Cooperative would no doubt have vigorously opposed the granting of a new licence.

In 1935 Gunn had operations at Wickham and Pearshape. A.H Miller began the Pearshape Cheese Factory and A E Gunn leased the newly built factory. The Pearshape factory was on the northeast corner of the junction of South Road and (A H.) Millers Road. A considerable quantity of the milk processed in Gunn’s Reedy Lake factory came from the East Wickham area. In 1936 Gunn employed a Mr. Medcraft to build a large timber and concrete factory on the southern side of the North Road just before the East Wickham Road begins. In July 1936 the King Island News reported: "Good progress is being made with the erection of the new cheese factory at East Wickham (adjacent to Mr Jasper Bell's homestead)". The new build was designed to be Gunn's main factory, with Ray Quinn as the cheesemaker. It was planned that whey butter would be made there, although that did not happen.

The effect on the Cooperative butter factory was alarming. In December 1932 it had 74 suppliers and was making twelve tons of butter a week. By December 1936, when all of Gunn's factories were operating, the Cooperative was down to 28 suppliers with a total of 1550 cows, while Gunn had 40 suppliers with 2340 cows, including 1020 of Gunn's cows. The three private cheesemakers, Blain, Haines and Snodgrass had a total of 500 cows. Output from the Cooperative had declined, from 338 tons in 1933, down to 229 in 1934, 176 in 1935 and 151 in 1936.

Gunn had been able to attract suppliers not only because of the general dissatisfaction with the Cooperative but also because he could pay higher prices. As the output of the Cooperative declined, overheads per ton of butter increased and the profits of the factory were eroded, thus making Gunn's prices even more attractive. In March 1937, Gunn's paid fourteen pence per pound of butterfat in milk, while the Cooperative paid twelve pence. Gunn's manager, J.M. Hyndes, was very helpful to suppliers, visiting any dairyman who asked for advice, while the Cooperative felt that the cost of a similar service to their suppliers would not be warranted. Desperately trying to return to profitability, the Cooperative made a belated attempt to diversify, applying to erect a cheese factory at East Wickham. Unfortunately, their application reached the Department of Agriculture after Gunn's, and the Department felt that although one cheese factory in the area was warranted, two were "not in the best interests of the industry." The Appeal Board upheld this decision. The Cooperative then applied for a dried milk licence, and when this too was refused they took the matter unsuccessfully to court. In 1937 they applied for a licence for their Loorana factory to produce cheese and casein as well as butter, but the factory was not satisfactorily equipped as it was registered only for butter production.

In 1938 the Cooperative applied to build a casein factory near Easton Johnson's property on the Pegarah Road. The factory was to be of weatherboard on top of a four-foot concrete wall, with cement floors and fibro cement interior walls and ceilings. But this application was refused on the basis that there were not enough cows to supply yet another factory, that the factory would cost a great deal more than the £2000 budgeted by the Cooperative, and that the market for casein was uncertain.

By this time, the number of dairy cows on the island had increased to 8000, and of the 380 tons of butter and 850 tons of cheese exported, A.E. Gunn Pty Ltd was producing half the butter (190 tons) and 90% of the cheese (760 tons) from its four factories. The competition between the two companies was intense, with each sending representatives around the island signing up farmers for support and forecasting the imminent closure of the other. Some people signed up to both. There was widespread support for amalgamation as competition was reducing the return to suppliers, but the terms proved the sticking point. Many people were in favour of a cooperative system, but the Cooperative had been inefficient in the past. One solution advanced was to make Gunn's manager, Jack Hyndes, the general manager of the cooperative. In 1937 Gunn agreed to sell, but although his assets were valued at £10,893, he demanded £12,800 and negotiations broke down. He then offered to buy the Cooperative for £5837 which the Cooperative regarded as too low a price.

On 18 August 1937 the Town Hall was packed for a ballot on the question. 147 people voted to transfer the Cooperative to Gunns, and 100 voted against it, but the constitution demanded a three-quarters majority so the stalemate continued. The disarray in the industry attracted the attention of successive Ministers for Agriculture, and in June 1938 Minister Robert Cosgrove finally achieved the breakthrough in negotiations. The King Island Dairy Factory Ltd was to go into voluntary liquidation to form a new company that would buy the assets of A. E. Gunn Pty Ltd for £15750, with the government lending £10,000. The extra money was to cover the cost of an additional plant that had been bought by Gunn since the valuation of the previous year. A meeting of almost 300 shareholders approved the plan, and the relief was tangible. According to the King Island News: "Immense enthusiasm was displayed and everything went with a swing, hardly a dissentient note being perceptible throughout the evening". The Cooperative's manager, Jack Brown, was appointed liquidator. The new company was to be called the King Island Cooperative Dairy Products Ltd. The dairy industry was now ready to go ahead. Production had increased threefold between 1933 and 1938, In the first year of operation, the new company made 683 tons of butter and 231 tons of cheese. A loss of 4000 pounds in 1939 was converted to a profit of the same amount in 1940. By 1940 the other private cheesemakers - Blain, Snodgrass and Haines had stopped making cheese because of the wartime federal government subsidy for dairying which was given only to those dairymen who supplied a central factory. However, two new families started up about 1940. They were the Lasts who had a small factory south of the Yellow Rock Road, and Billy Miller who utilised Gunn's old Pearshape factory.

Tomorrow: The changing ownerships of King Island Dairy cheese

PART ONE ORIGINS - TWO major problems had to be overcome before the dairy industry on King Island could become a reality.

The first of these was the prevalence of ‘coastiness’, caused by a noxious native species of pea (Swainsonia lassertifolia). Ingesting led to neurological and organ damage and fatality in cattle and sheep. The solution was stock observation and change of pastures.

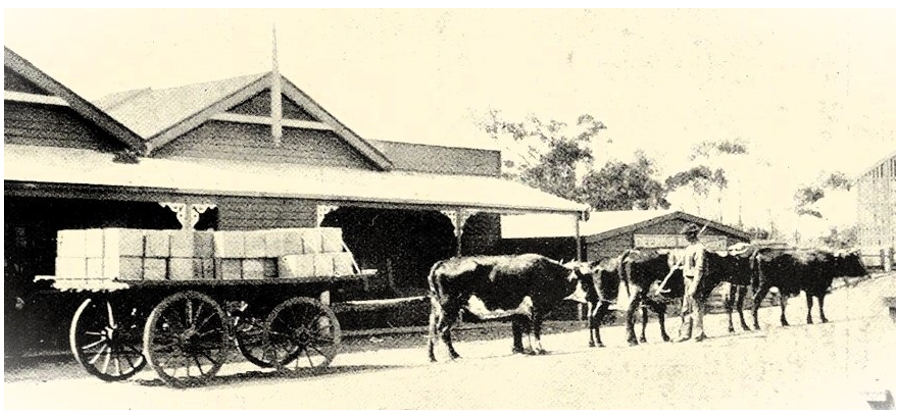

The second obstacle to any industry developed on the Island was/is dependence on shipping, With the arrival of F.H Stephenson and Thomas Gunn, came the building of the Yambacoona, by the newly formed King Island Shipping Co. Its first voyage was in 1898, providing inward and outward cargoes. By 1899 the ship was running fairly regularly to the island servicing a population of 155. Dairy farms were built around Surprise Bay, Fitzmaurice Bay, Porky Creek, Yellow Rock and Yambacoona.

King Island’s temperate climate made it ideal for dairying. Butter was produced for export from around 1892 and a cooperative structure emerged. The Weekly Courier reported in 1903 that D.B. McMahon at Sea View was one of the pioneer dairy farmers and had been producing butter for five to six years and said that in the best of the season, his herd of 70 cows averaged as much as nine or ten pounds (4-4.5kg) of butter per week. McMahon's butter was shipped to both the Tasmanian mainland and Melbourne before the turn of the century.

The Tasmanian Mail said that in 1899 regular shipments of butter were being sent from King Island to Strahan, and in October 1901 the Weekly Courier announced that the Yambacoona had taken 26 boxes of butter from the island and output was increasing week by week. The Examiner records in 1901, that for a long time, the settlers had wanted to start a creamery on the island and that this was taking shape as shares were taken up, and other settlers promised their support. The Emu Bay Times said that King Island was well adapted for the making of ‘First Class Butter’ and it sold from the ship's side at 1s. per lb.

On 7th February 1902, Messrs. Ern Cooper (Chairman) G. E. Robinson, D McMahon, J.M. Bowling, and H.R.D. Pearson were elected and formed a board and F. J. Robinson was appointed secretary and treasurer. Mr. Furguson, a Wynyard solicitor, was instructed to register the King Island Co-operative Dairy Factory Company Ltd. Messrs. J and T Gunn were requested to provide plans, specifications, and cost of erecting a suitable wooden building. Work on the foundations in Loorana began in May and the first milk was received at the King Island Dairy Factory on 28 August 1902.

The first manager was Mr. Roland Mollison from Burnie's Emu Bay factory. The Weekly Courier reported in January 1903 that the factory was "successful beyond anticipation". A ton of butter was being made every week from 500 cows and the King Island butter’s reputation was growing.

By June 1903 more suppliers bought their own separators and milk was no longer separated at the factory. Not all farmers joined the cooperative factory and some farmers continued to make butter and cheese privately. "Creameries" had been set up by Stephenson and Gunn at Yambacoona; Melville Stephenson at Loorana and Porky and Cooper and Sons at Whistler's Point. Archie Johnson at Wickham formed a side business that collected cream by wagon from the more distant farms at Surprise Bay, and a little over a year later he was travelling (22k) north and (29k) south twice a week.

The factory’s output grew rapidly. In March 1903 production was up a ton and a half per week and within a fortnight of the report, this increased to two tons weekly. The manager confidently predicted that this would rise to three tons per week in the new season, as most farmers were still using beef cattle not dairy breeds; the number of milch cows was expected to double to 1000; feed was available year-round, and the factory would operate through winter. By year end, production was at two and half tons and the island’s population had grown to 500.

Production constantly increased, and King Island butter was sold to different markets including to England and the dairy farmers’ cheques were also getting bigger. By the end of 1905 land was purchased to enlarge the factory site, included early refrigeration, and in 1908 the company was renamed King Island Co-operative Dairy Factory Co. Ltd.

When the war years arrived, a fifth of island’s the male population enlisted, and the labour-intensive dairy industry experienced shortages and downturns. Before 1920-21 the factory’s annual butter production was around 45 tons. This was similar to the previous ten years. Post-war the state government's Closer Soldier settlement scheme set up farms, many in the Yambacoona and Egg Lagoon districts in the north of the island. In the 1921-1922 season, the butter factory’s production almost trebled, with 132 tons being manufactured. By the end of the 1920s, the King Island factory was the largest butter producer in the state.

The ever-increasing growth put pressure on the 20-year-old building and equipment and a new concrete factory was built 150m north in 1924 and new equipment installed. Some butter and cheese makers continued to operate independently after the factory opening in 1902, largely because of transport difficulties, notwithstanding factory improvements, expansions and supply incentives. In 1905 the company resolved to pay a bonus of at least 50% of the yearly profits to those suppliers who had not sold butter, cream, or milk outside the company.

The larger concerns included the Bowling family well-known for the butter made at their various properties. Around 1900, Hugh Bowling of Surprise Bay had a contract to supply butter to a Hobart biscuit factory. McMahon made cheese at Boggy Creek 1900-1910, and (most unusually) Stilton cheese was made by Carlson at Yambacoona Estate, soon after the turn of the century.

Tomorrow: Part 2, The Cheesemakers.

Add new comment