Rising rates give farms no value

NEVER before has the case for local government rationalisation or reform been so clearly needed.

Unrestrained rate increases combined with the six-yearly revaluation of properties, have only further added non-productive costs to farm businesses.

Primary producers face increasing costs with no com mensurate growth in services provided.

Local government in Tasmania, despite the best of intentions from council staff and elected members, surely can not continue to operate long term under these inherently unfair and unsustainable revenue models.

Farmers operating in small municipalities are at a further significant financial disadvantage, not because of their soil types, the rainfall, commodities produced or other aspects of the farm business, but because they are demonstrably picking up a significant part of the tab for others in those small councils.

One key reason lies in the differential between councils and how rates are levied.

Despite being in the same state, a farmer in the southeast is charged very differently to one in the northwest, the Midlands, the Highlands or the northeast.

The continual sticking point is applying the annual assessed value (AAV).

It is on all rates notices, irrespective of the size or use of the property.

This calculation is based upon an estimated yearly rental value for the property, which in Tasmania is universally calculated as 4 per cent of the capital Rising rates give farms no value value.

This might work in the residential suburbs of Launceston, Hobart and Devonport, However, its variable application to primary producers is inequitable.

The 4 per cent AAV rate is appropriate for a residential home, but if your farm was worth $10 million and you could get $400,000 a year to rent it out – would you farm it or rent it out? Many would take the latter.

Based on this 4 per cent number, councils then apply their AAV rate to determine the figure a farmer is charged.

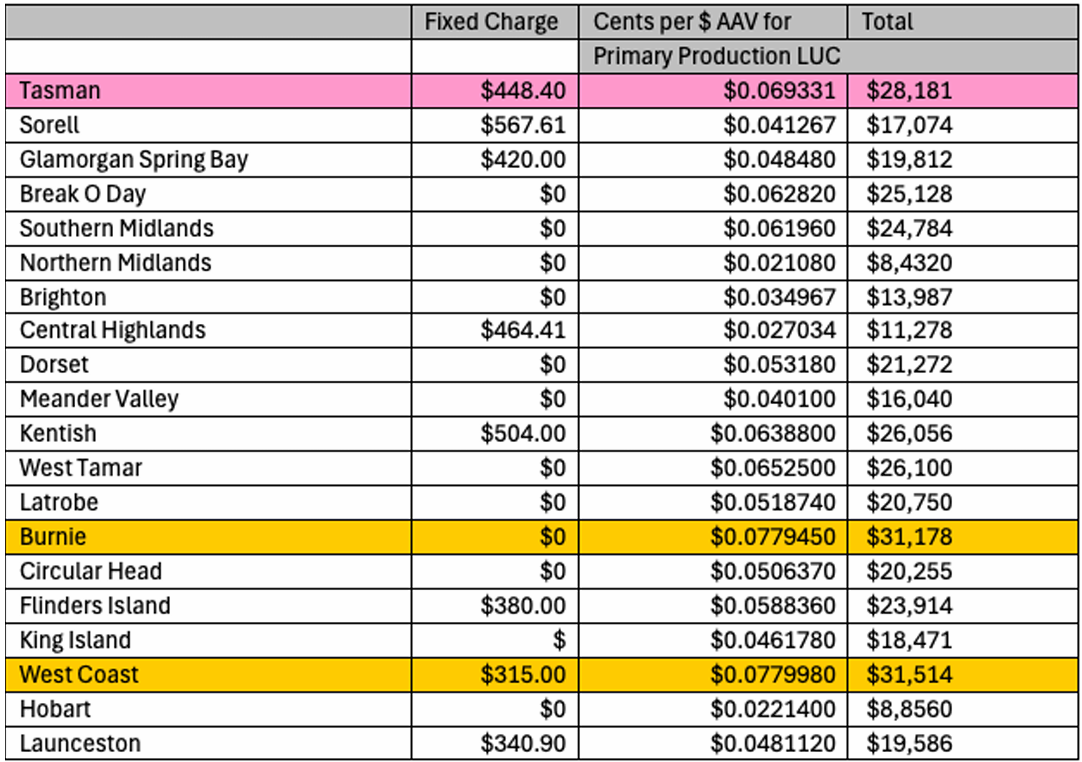

The table above shows the calculation for each municipality based on a farm value of $10 million.

While $10 million might sound like a very high number, most farms that are standalone businesses would have that value as a minimum. The formula is relatively simple, 4 per cent of the capital value of the farm, then multiplied by the AAV rate that each council sets.

For example, a $10 million farm in the Circular Head municipality would have an AAV value of $400,000, which is then multiplied by the council’s AAV rate of $0.050637, which gives a rate charge of $20,255 per year. Some councils add a fixed charge to that as well – some do not.

Not only do farmers have to contend with the annual increase according to the AAV calculation, the revaluation of farms every six years means that farmers are effectively taxed on an unrealised capital gain.

This is incredibly disproportional to the reality of doing business, as many family properties will never be sold – indeed many have been in the same family since the early 1800s.

The value of the asset is increased, but that increase in value is not reflected in the actual income of the farm. It’s not like the price of potatoes, lamb, or milk has increased because your farm has been revalued!

What this exercise demonstrates very clearly is that a farm of the same value will be taxed at significantly different rates according to arbitrary lines on a map.

Governments would never do this with any other form of taxation – why is this accept able for primary producers?

The clear answer is for government to take the lead and do several things.

The first and possibly the easiest is to reduce the AAV figure applied to land used for primary production – 4 per cent is not an accurate reflection of the rental return a farm would be worth.

The second is to standardise the council-applied AAV figure so that it is consistent across the entire state.

That this figure varies by so much is not in the interest of primary production in this state and reflects badly on our ability to have a competitive agricultural sector.

The other and more difficult, politically at least, is to rationalise local government in Tasmania.

This means fewer councils covering larger areas and delivering services com mensurate with the money paid. Primary production in Tasmania has never been so challenging – international factors are placing increasing pressures on a farmer’s capacity to farm profitably, not to mention increasing regulation and supply chain costs.

Profitable farming is the cornerstone to the economic and social health of our regions and every effort should be under taken by all three levels of government to ease the cost of doing farming business cri sis in Tasmania.

Add new comment